Sensorimotor Psychotherapy vs. Somatic Experiencing: A Guide for Trauma Therapists in Australia

If you’re here, you probably already know that trauma is more than a collection of symptoms or a diagnosis, it’s an experience that lives in the body.

As therapists, we see it every day. Clients come in talking about feeling stuck, numb, or overwhelmed, and sometimes words alone just don’t reach the places that hurt. That’s why so many of us have turned to body-based approaches like Sensorimotor Psychotherapy (SP) and Somatic Experiencing (SE).

But here’s the thing: it can be confusing to figure out how they differ—or even if one is “better” than the other. I hear this question a lot: “Should I train in SP or SE? Which is right for my clients?”

The truth? There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Both approaches have strengths. And both can help clients learn to live more fully in their bodies after trauma.

This guide is for therapists, like you, who want to understand the differences—and similarities—between Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Somatic Experiencing. I’ll break it down in a way that’s honest, evidence-based, and grounded in both clinical experience and the voices of the people we work with.

So grab a cup of tea (or coffee—no judgment) and settle in. Let’s explore how these approaches can shape your work with trauma survivors.

Want the condensed version - scroll down to the end and read the summary FAQ’s from this blog!

Why Talk About Body-Based Approaches?

Trauma lives in the body. It’s not just something that happens to us; it’s something that gets stuck inside us. You know that feeling when a client talks about being “on edge,” or says, “I just feel numb”? That’s the body telling its story.

A lot of traditional talk therapies focus on thoughts and emotions—and that’s important. But sometimes talking just circles the problem. Clients might understand what happened, even why it happened, but still feel like they’re trapped in that old story.

That’s where body-based approaches come in. They help us connect to the places where trauma lives—tight shoulders, a clenched gut, frozen limbs. They help people make sense of the stuck places, the places where they couldn’t run or fight or ask for help. And they give us a way to process those experiences—not just with words, but with movement, breath, and gentle attention.

Research backs this up. Bessel van der Kolk (2014) talks about how trauma can hijack the nervous system, leaving people stuck in fight, flight, or freeze. Pat Ogden’s work shows that paying attention to the body helps clients move through these states more safely. Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing model is based on this same idea—that trauma gets trapped in the body and can be released by paying attention to sensations.

But it’s not just about research. Clients themselves often tell us that they feel disconnected from their bodies, or that they can’t trust their own sensations. They might say, “I don’t even know what I feel.” Or, “I feel like I’m watching life from the outside.” When we bring the body into therapy, we help clients come home to themselves. And that’s powerful.

So, before we get into the nitty-gritty of how Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Somatic Experiencing differ, it’s worth remembering why we’re even talking about the body in the first place: because that’s where trauma lives, and that’s where healing begins.

A Quick Overview of Each Approach

Before we get into comparing the nuts and bolts, it helps to have a snapshot of what each approach is all about.

In this section, we'll explore the foundations of Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Somatic Experiencing, two prominent approaches in trauma therapy. We'll also discuss the importance of somatic therapy in addressing trauma-related issues, particularly the interplay between psychological and physiological processes (Ogden, Minton, & Pain, 2006; Levine, 2010).

Defining Sensorimotor Psychotherapy

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy is an innovative approach to trauma therapy that integrates bodily experiences with cognitive and emotional processing. Developed by Pat Ogden in the 1980s, this method recognizes the profound impact of trauma on the body and nervous system (Ogden et al., 2006).

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, or SP for short, grew out of somatic traditions, attachment theory, and mindfulness. The idea is pretty simple but powerful: the body holds memories of trauma, and these memories can show up in posture, tension, or movement patterns. SP brings the body into the therapy room, working alongside thoughts and emotions, to help clients process stuck experiences.

One thing that sets SP apart is its structured training levels. Level 1 focuses on stabilising the nervous system and building resources, like teaching clients how to feel safe enough to explore trauma. Level 2 dives into developmental and attachment trauma stuff that often starts early in life and shapes how we relate to others. Level 3 is all about integrating what you’ve learned, bringing in advanced skills, and refining your clinical work.

SP is a relational therapy. It’s about noticing how clients respond to you in the room. This can include their posture, gestures, or even a sudden change in breath. These moments can hold clues to their trauma history. And by working with these body stories, you help them rewrite the narrative.

At its core, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy focuses on the interplay between physical sensations, movement patterns, and psychological processes. This approach helps clients become more aware of their bodily responses to trauma triggers and learn to regulate these responses effectively.

Furthermore, SP invites exploration of posture, muscle tension, and movement habits that may have developed as protective adaptations. By increasing clients’ awareness of these somatic patterns, therapists can help them renegotiate trauma responses and cultivate more adaptive ways of inhabiting their bodies.

Overview of Somatic Experiencing

Somatic Experiencing, or SE, was created by Peter Levine in the 1970s. Levine was fascinated by how animals recover from life-threatening situations. Think about a deer that shakes after a near-miss with a predator…it’s a way to reset the nervous system. Levine wondered why humans often stay stuck instead of shaking it off.

SE is all about helping clients complete these “stuck” defensive responses. It’s less focused on talking and more on noticing bodily sensations—like heat, tingling, or tightness—and following them through to resolution. SE therapists talk a lot about “pendulation”—moving between safety and challenge in manageable doses, and “titration,” which means breaking down big experiences into smaller, digestible pieces.

SE has a flexible training structure, too. It’s offered in modules, so therapists can move at their own pace. There’s a strong emphasis on learning to work with the nervous system, so you can help clients gradually discharge that survival energy.

The primary goal of Somatic Experiencing is to help individuals complete these natural physiological responses that may have been interrupted during traumatic events. By doing so, it aims to release stored trauma energy and restore the body's natural self-regulation capacity. Somatic Experiencing emphasizes the client’s subjective experience of safety. Using resourcing techniques and careful pacing, it helps clients gradually build their capacity to tolerate distressing sensations without becoming overwhelmed.

Similarities Between SP and SE

You might be wondering: if Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Somatic Experiencing both work with the body, aren’t they basically the same thing? It’s a fair question—and the answer is: kind of. Both approaches share some core ideas, and that’s why they can feel similar at times.

First, both SP and SE focus on bottom-up processing. That means they pay close attention to what’s happening in the body. Both approaches focus on sensations, movements, or subtle shifts in breath and use that as the starting point for therapy. The idea is that the body often knows more than the thinking brain, especially when it comes to trauma.

Both approaches also use tracking. Tracking is the therapist’s skill in noticing what’s happening in the client’s body. Whether it’s a clenched jaw, a shaky leg, or a shift in tone of voice, both SP and SE therapists tune in to these signs as pathways to healing.

Safety is another big overlap. Both SP and SE understand that trauma therapy can feel overwhelming, so they emphasize creating a sense of safety and trust. That might mean slowing things down, resourcing, or checking in regularly to make sure clients don’t feel flooded.

Another similarity? Both approaches help clients reconnect with the present moment. Trauma often pulls people into the past, replaying memories like a stuck record. By helping clients notice their bodily sensations right here, right now, SP and SE can gently bring them back to a sense of aliveness and agency.

And finally, both SP and SE integrate well with other therapies like Internal Family Systems (IFS), EMDR, or more traditional talk therapies. Therapists often blend techniques, depending on what feels right for each client.

And here’s something I find really special: Pat Ogden and Peter Levine have taught together. Their collaborations have always been grounded in a deep respect for each other’s work and a shared belief that the body holds the key to healing trauma. It’s a reminder that even though these approaches have evolved in different directions, they share common roots and that’s a beautiful thing.

So, while they have their own styles and techniques, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Somatic Experiencing share a deep respect for the body as a gateway to healing. And that’s a pretty powerful thing.

Key Differences—The Nuts and Bolts

Now that we’ve talked about what Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Somatic Experiencing have in common, let’s get into what makes them different. Because while they’re both body-based, the ways they understand and work with trauma aren’t exactly the same. And that’s what makes this field so rich.

Philosophy and Theory

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy (SP) leans heavily into the relational piece. It’s not just about helping the client feel what’s happening in their body; it’s about noticing how those body responses show up in the therapy relationship. For example, a client might shrink away slightly when you ask a question, or tighten their jaw when talking about a memory. SP sees those moments as part of the story the body is telling. It’s also deeply informed by attachment theory, so therapists pay close attention to early relational patterns, like how a client might avoid eye contact or feel unable to ask for help.

Somatic Experiencing (SE), on the other hand, is grounded in survival physiology. Peter Levine was inspired by how animals naturally “discharge” energy after a threat, for example, like a gazelle shaking after an escape from a lion. SE therapists look for incomplete defensive responses, like fight, flight, or freeze—that got stuck in the client’s body during trauma. The goal is to help the client complete those responses, so the nervous system can settle. SE is less focused on the therapeutic relationship itself and more on the client’s internal experience.

Techniques and Tools

In SP, therapists often use body reading, as a way of observing posture, movement, and gestures to understand how trauma lives in the body. They might gently ask clients to explore a posture or movement, notice what happens, and then work with that awareness.

Mindfulness is woven throughout, helping clients stay present with sensations. SP also uses movement experiments, which can include small shifts in posture or guided movements to help shift old patterns. There’s also an integration of parts work—acknowledging the different “parts” or aspects of a client’s experience, although it’s not the same as full IFS.

A key strength of Sensorimotor Psychotherapy lies in its structured training pathway, which includes a dedicated focus on developmental and attachment trauma in Level II training. This level provides an in-depth exploration of how early relational experiences shape the nervous system and impact clients’ capacity for regulation and connection. Therapists are taught to recognize and work with attachment-related patterns such as disorganized attachment, insecure strategies, and relational defenses through a somatic lens. This focus on developmental trauma equips practitioners to address complex trauma presentations with greater nuance and attunement, deepening their capacity to support clients in repairing relational injuries and building healthier attachment templates.

SE, meanwhile, focuses on pendulation, helping clients move between sensations of distress and sensations of safety—and titration, which is about taking small steps to avoid overwhelming the client. SE therapists often ask clients to track subtle sensations like warmth, tingling, or tightness, and follow those sensations through to a natural release. It’s less structured around body reading and more about following the client’s internal experience moment to moment.

Both approaches pay attention to dissociation, but they handle it a bit differently. SP might use gentle movement or relational contact to bring a client back into the body, while SE might slow things down even further, using micro-movements and subtle shifts to gradually re-establish connection.

Core Principles of Sensorimotor Psychotherapy

What sets Sensorimotor Psychotherapy apart is its grounding in six guiding principles, which shape both its theoretical foundation and practical application (Ogden et al., 2006). These principles foster a deeply respectful, holistic, and relational approach to therapy:

1. Organicity

This principle recognizes the inherent self-organizing wisdom of each person. SP respects the client’s natural capacity for healing and growth, viewing symptoms as adaptive rather than pathological. Therapists act as facilitators rather than fixers, supporting clients’ unique processes rather than imposing change.

2. Non-Violence

Non-violence underpins the therapeutic stance of compassion, acceptance, and respect. Therapists avoid imposing their agenda or interpretation, instead prioritizing the client’s pace and safety. Symptoms are approached with curiosity rather than judgment, supporting the client’s autonomy and dignity.

3. Unity

Unity reflects the interconnectedness of all aspects of the self—body, mind, and spirit—as well as the individual's connection to others and the environment. SP encourages integration of these dimensions, promoting a cohesive and authentic sense of self that supports relational and social well-being.

4. Mind-Body-Spirit Holism

SP embraces the holistic nature of human experience, recognizing that psychological well-being is intimately linked with physical and spiritual health. Sessions are designed to address all dimensions, integrating bodily sensations, emotions, thoughts, and meaning-making to support comprehensive healing.

5. Mindfulness

Mindfulness in SP involves cultivating present-moment, non-judgmental awareness of internal experiences. This capacity allows clients to observe their sensations, emotions, and thoughts with curiosity rather than avoidance, fostering self-regulation and deepening their understanding of trauma responses.

6. Relational Alchemy

Relational Alchemy highlights the transformative potential of the therapeutic relationship. SP sees the therapist-client dynamic as a microcosm for exploring attachment, trust, and emotional safety. Through authentic, attuned interactions, clients experience relational healing and develop new ways of being in relationship with themselves and others.

These principles differentiate Sensorimotor Psychotherapy from other somatic therapies by creating a relational, process-oriented, and holistic approach that aligns with contemporary trauma theory and practice.

Training and Supervision

The training pathways are different too. SP is taught in three levels: Level 1 focuses on stabilisation and building resources; Level 2 moves into developmental and attachment trauma; Level 3 focuses on integration and advanced skills. Each level builds on the one before, and supervision is woven throughout. It’s a more linear path, which some therapists find helpful for building confidence and structure.

SP also offers a number of different training options including online, hybrid In person and online, and fully in person.

You can find out more about the SP level I training here.

SE is structured in modules, usually split into beginner, intermediate, and advanced levels. It’s a bit more flexible, so therapists can sometimes tailor their training journey to fit their learning pace and schedule. .

Both training programs are rigorous and require commitment, but each has its own rhythm and focus. It often comes down to what fits your learning style and the needs of the clients you work with.

When Might You Choose One Over the Other?

You might be thinking, “So which one’s right for me and for my clients?” And honestly, that’s the million-dollar question. The answer’s not always straightforward. It often comes down to the kind of clients you see, your personal style as a therapist, and what feels most intuitive to you.

Let’s break it down a bit.

If you’re working with clients who have complex trauma like chronic relational trauma or developmental wounds from childhood. Sensorimotor Psychotherapy might feel like a better fit. Its strong focus on attachment patterns and how those show up in the body means it’s well-suited to exploring long-standing relational wounds. SP’s relational approach can help you gently explore how early experiences shape the body’s responses and how those patterns might still be playing out in the therapy room.

But SP isn't limited to complex trauma; it's also effective for shock traumas—those sudden, overwhelming events like accidents or assaults. SP employs a technique known as sequencing, which involves guiding clients through the body's natural process of discharging and integrating the energy associated with traumatic events. This method helps clients process the physiological responses that were activated during the trauma but weren't completed at the time.

Moreover, SP addresses the concept of incomplete defensive responses. During a traumatic event, an individual might have an instinctual urge to fight, flee, or protect themselves, but circumstances may prevent the completion of these actions. SP facilitates the completion of these "acts of triumph," a term introduced by Pierre Janet, which refers to the successful execution of defensive actions that restore a sense of agency and mastery.

If you’re drawn to working with clients who present with symptoms of PTSD or single-incident trauma like accidents, assaults, or medical trauma Somatic Experiencing can be incredibly effective. SE’s focus on completing stuck defensive responses and discharging survival energy can bring relief to clients who feel trapped in fight, flight, or freeze. SE’s flexible structure is great for following the client’s natural rhythms, especially when working with high arousal states.

Your own style matters too. Some therapists appreciate the structure and layering of SP’s levels, which build a solid foundation grounded in neuroscience, attachment theory, and neurobiology. That framework can be especially helpful when working with complex developmental trauma. SP’s emphasis on the therapeutic relationship and its systematic approach help therapists feel confident and supported as they guide clients through deeply rooted patterns. SE, on the other hand, offers a more fluid, client-led approach that some therapists find helpful for certain types of trauma work.

Accessibility can also play a part. Depending on where you’re based, one training might be easier to access than the other. (A quick shout-out here: Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Australia is working hard to make SP more accessible across the country.)

At the end of the day, it’s not always about choosing one or the other. Many therapists blend tools from both approaches to create a style that fits their clients—and themselves. As you are reading this blog, you may also know that I the writer - Natajsa Wagner, am both a certified sensorimotor Psychotherapist and Somatic experiencing Practitioner!

Comparative Therapy Techniques

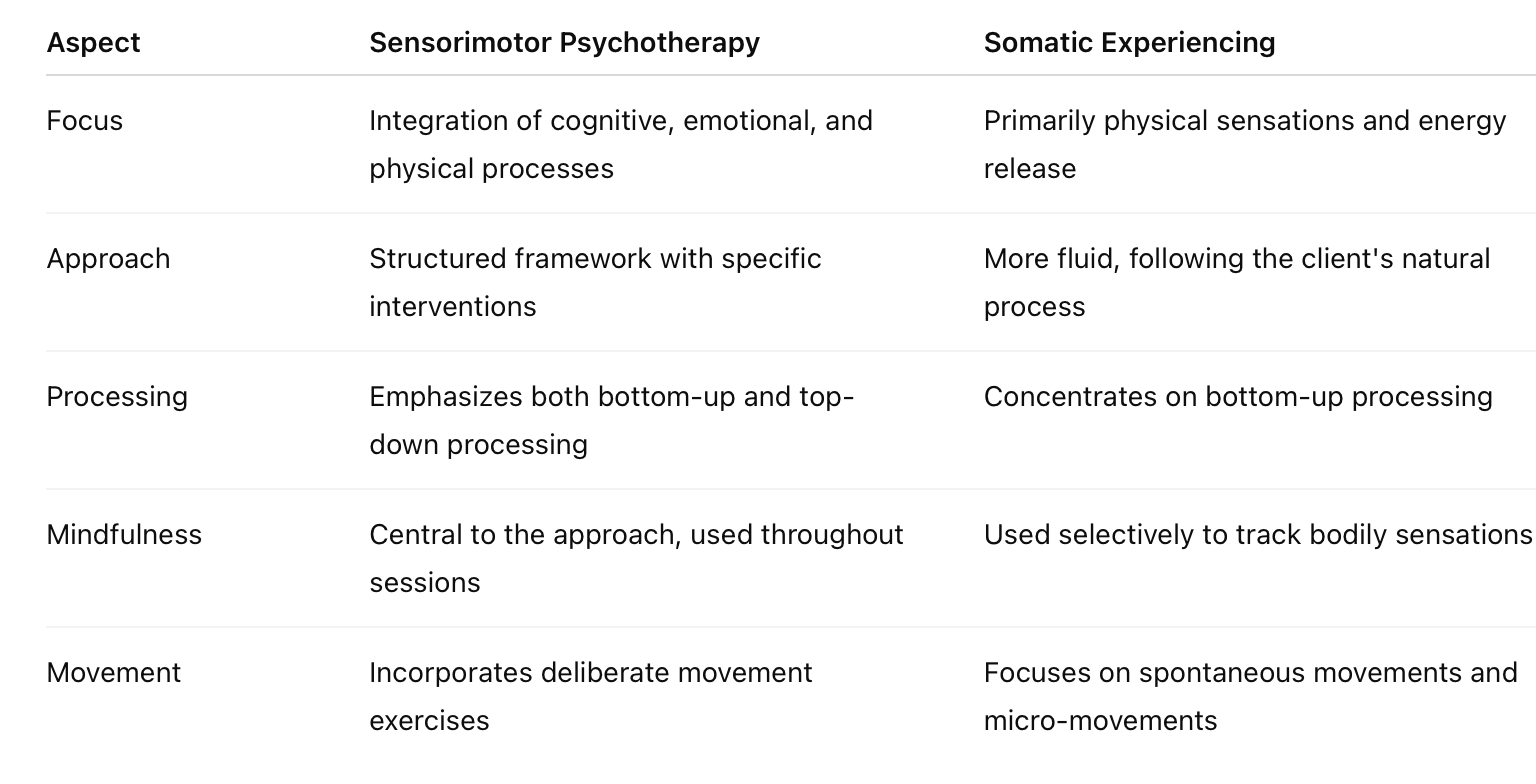

When comparing Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Somatic Experiencing, several key differences emerge in their therapeutic techniques:

Both approaches share a commitment to working with the body in trauma therapy, but their specific techniques and emphases differ, allowing therapists to choose the most appropriate method for each client's needs.

Integrating Both—Is It Possible?

Sometimes people ask me, “Can I use both Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Somatic Experiencing in my practice?” And honestly, yes, you can. It’s not about choosing sides; it’s about finding what works best for your clients, and what feels most authentic to you as a therapist.

Many therapists do exactly that. They might draw on SP’s structured approach to understand a client’s attachment patterns and relational history, then weave in SE’s gentle, titrated focus on discharging survival energy when the moment calls for it. Some therapists find that having both frameworks in their toolkit helps them respond more flexibly to whatever arises in a session.

Of course, blending modalities takes care and respect. It’s important to have a solid foundation in each approach before mixing them together. That means completing the training, getting supervision, and making sure you understand the ethics and scope of each model. It’s not about cherry-picking techniques, but about deeply embodying the principles of each approach so you can integrate them skillfully.

In my own work, I’ve found that integrating both SP and SE can create a richer, more nuanced experience for clients. Having both options can feel like having a map and a compass you can plan your route and also adapt as the terrain shifts.

At the end of the day, integration is about serving your clients. It’s about listening to them, being guided by their needs, and staying open to learning. And that’s what makes this work so rewarding.

Advantages of Sensorimotor Psychotherapy

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy offers several advantages:

Comprehensive Integration: Combines bottom-up and top-down processing.

Relational Alchemy: Prioritizes the healing potential of the therapeutic relationship.

Attachment Focus: Integrates attachment theory for relational trauma.

Structured yet Flexible: Provides systematic interventions while respecting client organicity.

Mindfulness Emphasis: Cultivates self-awareness and regulation.

Holistic Orientation: Incorporates mind, body, and spirit for integrated healing.

Integrating Sensorimotor Psychotherapy into Practice

To incorporate Sensorimotor Psychotherapy into practice:

Complete comprehensive training and certification.

Introduce basic body awareness exercises.

Gradually incorporate advanced techniques.

Apply SP principles to enhance existing modalities.

Cultivate personal mindfulness to model regulation.

“Integrating Sensorimotor Psychotherapy into your practice can significantly enhance your ability to help clients process trauma and develop resilience,” notes Dr. Pat Ogden (Ogden et al., 2006).

Final Thoughts

There’s no one right way to work with trauma. Every client brings their own history, needs, and ways of making sense of the world, and every therapist brings their own experience, training, and style.

Continued education in trauma therapy techniques is also crucial for effective and ethical practice. Therapists are encouraged to attend workshops, engage in supervision, stay current with research, and explore complementary modalities.

“The field of trauma therapy is constantly evolving. Staying current with new developments is not just beneficial—it’s essential for providing the best possible care to our clients,” emphasizes Dr. Bessel van der Kolk (2014).

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Somatic Experiencing are both powerful approaches that honour the wisdom of the body. SP’s structured, relational approach, rooted in neuroscience, attachment theory, and developmental perspectives makes it especially well-suited for complex trauma that’s woven through a person’s sense of self. SE’s fluid, sensation-focused method is a gentle, adaptable way to help clients complete stuck defensive responses.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned from years in this work, it’s that trauma healing is not about finding the “perfect” modality—it’s about showing up with curiosity, compassion, and a willingness to learn. It’s about building a strong therapeutic relationship and helping clients feel safe enough to explore their own stories, both the spoken and the unspoken.

I hope this guide has given you a clearer picture of how Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Somatic Experiencing work, where they overlap, and how they differ. If you’re curious to learn more about SP or SE, or how to integrate them into your practice, I’d love to hear from you.

And here’s the thing: no matter which path you choose, remember that your presence and attunement are the most important tools you have. Because at the heart of this work, it’s the human connection that heals.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the difference between Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Somatic Experiencing?

A: Sensorimotor Psychotherapy (SP) blends body awareness with attachment theory and relational dynamics, making it especially helpful for developmental and relational trauma. Somatic Experiencing (SE) focuses on discharging stuck survival energy from shock trauma, helping clients complete incomplete fight, flight, or freeze responses.

Q: Is one approach better than the other?

A: It really depends on your clients and your own style as a therapist. SP’s structured, relational approach is often recommended for therapists working with complex trauma, while SE’s flexible, client-led approach can be great for single-incident trauma or high-arousal states. Both approaches are powerful in different ways.

Q: Can Sensorimotor Psychotherapy be used for shock trauma too?

A: Absolutely. SP includes tools like sequencing, which helps clients process trauma activation step-by-step through the body. It also supports the completion of defensive actions that couldn’t be completed at the time of trauma—something Pierre Janet called “acts of triumph,” also known as Reinstating Active Defenses (RAD). This helps clients regain a sense of agency and safety.

Q: Can therapists integrate both SP and SE into their practice?

A: Yes, many therapists find that combining elements from both approaches deepens their work with trauma survivors. It’s important to have a solid foundation in each model—through training and supervision—before blending them together.

Q: Where can I train in Sensorimotor Psychotherapy in Australia?

A: Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Australia offers Level 1, 2, and 3 trainings across the country. Our programs are designed for therapists who want to build a strong, body-based approach to trauma therapy. You can learn more and join the waitlist on our website.

References:

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Levine, P. A. (2010). In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

Fisher, J. (2017). Healing the Fragmented Selves of Trauma Survivors. New York: Routledge.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. New York: Viking.